Trinidad: Nature & Wildlife

Trinidad: Nature & Wildlife

Art Workshop

Immerse your senses into the bounty of the tropics and you will find endless inspiration to breathe new life into your artwork. Join me during this wonderful upcoming workshop presented by Victor Emanuel Nature Tours (VENT).

Click this link to the VENT website for details, itinerary, pricing and more information about this exciting tour and workshop.

This workshop and tour is geared toward beginner and advanced nature enthusiasts interested in ample opportunities to capture wildlife through art or journaling while being immersed in a tropical setting – the world famous Asa Wright Nature Centre. Whether you are a birdwatcher who has always wanted to draw birds in the field but has not found the right setting, or an avid journal keeper, a blossoming watercolorist or an experienced landscape painter, this workshop will offer a balanced combination of structure and freedom to create art at your own pace. Most important, the abundant tropical birds, stunning rainforests of Trinidad and rustic setting of the estate house will grant you long-lasting inspiration.

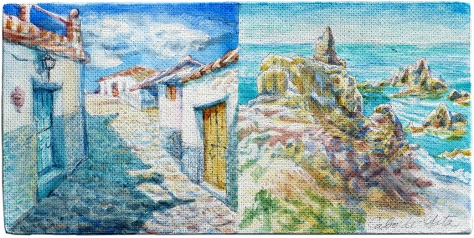

Detail of a sketch (5.75″ x 12″) done at the Asa Wright Nature Centre veranda, Trinidad. This watercolor was started during June of 2012, and then finished during February of 2016. Crested Oropendolas are colonial breeders, and weave long basket-like nests suspended from the branches of large trees that hang over the Arima Valley.

This workshop will be centered on a six-night stay at Asa Wright’s great estate, lodge and preserve. The historic plantation house has been visited by a number of renowned ornithologists and artists including William Beebe, David Snow, and renowned American painter Don Eckelberry, who depicted a number of Trinidad’s birds and their habitats. As with many other researchers and artists, they were attracted to the wide array of tropical species representative of New World bird families found at the preserve, including trogons, manakins, motmots, parrots and antbirds, and the lush habitats teeming with epiphytes, lianas and blooms.

Asa Wright Nature Centre is the ideal location for a nature art workshop because the ample veranda at the estate is a “living” studio that offers close views of feeders that attract many birds and other wildlife, with vistas of the expansive Arima Valley, and access to trails into tropical forests. Without leaving the veranda, participants will observe hummingbirds of several species including Tufted Coquette, tanagers and honeycreepers such as Blue Dacnis, Bananaquits and many other colorful feathered gems. Ample subject matter is readily available to the nature artist, and the facilities at the preserve offer a variety of settings for those interested in working in close proximity to the outdoors.

Detail showing Crested Oropendolas (Psarocolius decumanus) engaged in elaborate nuptial displays that include bowing from their perches and from overhanging nests, and displaying their bright yellow tails and rusty vents.

Participants are invited to immerse their senses into the bountiful nature of Trinidad to find new inspiration for their artwork, and to work in a supportive setting, surrounded by like-minded individuals. The goal is to create work influenced by the field experience with a focus on personal growth. This workshop is ideal for those that have already developed a personal craft, and for those who would like to play with line and color, learn new techniques, and participate in constructive group sessions. Participants are encouraged to work with the materials of their choice and on the subject matter that most interests them. Emphasis will be placed on the depiction of fauna, flora and habitat from direct observation. Sketching or painting while viewing wildlife through a spotting scope or binoculars can be quite effective. Those who wish to work from their own photographs may do so. Each participant is responsible for bringing his/her own optic and photographic equipment and art materials.

Click to enlarge – Various sketchbook studies of Golden-headed Manakin males engaged in lekking behavior, which includes sideways dancing, foot-tapping and sliding along display perches, vowing and chest-puffing, wing-vibrating, and darting up and down branches. Most of the sketches were done on February 2012, with touch-ups during February 2016 at leks within the Asa Wright preserve.

Throughout this workshop, you will be guided by experienced naturalists and artists. The leaders have extensive experience in the visual arts when it relates to nature, particularly the depiction of birds in their habitats, and have acquired significant experience by working in the field. The workshops, hikes and presentations offered during this tour are designed to give nature artists enough structure and support when needed, and the freedom and flexibility for those seeking independence. During our morning hikes, we will have an opportunity to study the birds, butterflies and plants of the preserve, and become acquainted with the trails that lead to the leks of manakins and the haunts of bellbirds. Your guides will be field sketching, painting or journaling right alongside participants, demonstrating techniques, leading group exercises, and working with those needing individual help. You will have the option of taking part in structured exploratory workshops for the strengthening of drawing and composition skills, or follow your own pace. More importance will be placed on process rather than product. Participants have the liberty to focus on simple projects like creating a series of loose sketches throughout the tour, or dedicating their entire time to a sketchbook, or developing as ambitious a series of works as desired. There will be plenty of free time to explore the grounds on your own and find subject matter of your liking, to study the birds and plants at your own leisure, or to spend most of the time participating in structured workshops.

Field trips away from the lodge should produce encounters with a number of particularly spectacular tropical birds and landscapes. Throughout the tour we will be keeping a detailed list of all our observations, as is done in traditional birding tours. Each evening we will have recap sessions during which we will share our progress, give feedback to those who desire it, and learn about other artists. Trinidad is a wonderful entrée to the natural history of the American tropics and its marvelous biodiversity. Birders, naturalists, sketchers and painters alike will find the Asa Wright Nature Centre inspiring, and this workshop will offer a broad range of options for both beginners and advanced artists.

TRINIDAD: NATURE & WILDLIFE ART WORKSHOP

FEBRUARY 23 – MARCH 1, 2017

More blog entries about sketching in Trinidad & Tobago:

To find our more about tours led by Rafael Galvez visit the

Victor Emanuel Nature Tours website.